The

University of Minnesota Duluth

Department of Theatre

presents

The Philanthropist

Music Source: Perpetuum Mobile, by The Penguin Cafe

by

Christopher Hampton

Directed by Rachel Katz Carey

Scenic Design by Jeff Johnson

Costume Design by Stacy Mittag

Lighting Design by Mark Harvey

March 13-29, 2003

Dudley Experimental Theatre

Lighting Design Approach

It’s been a while since a play, on first reading, affected

me emotionally as much as Christopher Hampton’s The Philanthropist.

Perhaps it was because Hampton sets his play in two communities I hold dear:

England and higher education. The characters speak in a vernacular I admit I

aspire to, but Hampton reveals a much more bleak image of a culture that assumes

its own intelligence as the highest plane of universal wisdom.

The scenic designer placed the acting space in the corner of the Dudley Experimental

black box with the audience on two adjacent sides of the rectangular set. I

noticed the blocking mirrored the scenery in its angular, even maze-like movements

and wanted the lighting to emphasize this angularity with four distinct functions

of area light set at right angles to one another. The key light for each scene

came from a high back light, indicating time of day. Evening and night scenes

used warm high back light to emphasize the illusion that light was coming from

the many practicals on the stage.

In contrast, day time key light was a high cool white back light.

Two sets of fill light were used for visibility for the audience, each at right

angles to the other. Color was a medium cool blue, reinforcing the idea of the

play being set in England in the late fall.

The production called for six scenes and the lighting helped establish time of day for each scene.

Scene 1 - Early evening

Scene 2 - Early evening (identical to the previous scene)

Scene 4 - Morning

Scene 6 - Early evening (again identical to Scene 1)

To create different looks for each of these scenes, the four lighting functions

were used in contrast to one another. In Scenes 1, 2, and 6, warm high back

light and front fill were balanced with one another. In Scene 3, less front

fill indicated time had moved deeper into the night.

Scene 4 used window patterns of light in warmer tones to indicate a rising sun.

Cool white high back light was balanced with cool front fill to indicate morning.

Scene 5 used the brightest levels of cool white high back light and the least

amount of fill, enhancing the idea of the brightest time of day as well as sculpting

actors’ faces and bodies more profoundly.

A special was also included to light Philip during the scene shift between Scenes 5 & 6.

REVIEW

Posted Saturday, March 15, 2003

Actors in The Philanthropist Can Give Only So Much

by PAUL BRISSETT

for THE DULUTH NEWS TRIBUNE

The Philanthropist is either misnamed or titled with sly irony. Christopher

Hampton's play, which opened Thursday at the University of Minnesota Duluth's

Marshall Performing Arts Center, is about a man so terrified of offending people

that he offends by his very lack of self. Hampton's intent was to invert Moliere's

The Misanthrope, an idea he develops with skilled writing, wit and engaging

characters. To these assets the UMD Theatre production adds first-rate staging

and solid acting. But at its core, The Philanthropist is hollow and ultimately

unsatisfying.

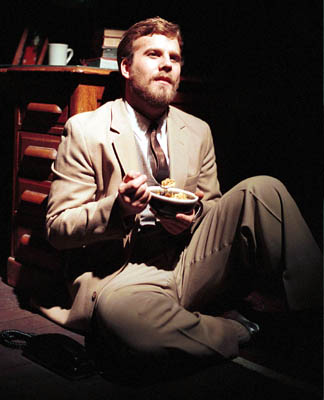

The title character is Philip, a scholar of an obscure subspeciality of English

at an unnamed but venerable English university who explains that he can't teach

literature because he has "no critical faculties whatsoever." Matthew

Salmela does an impressive job with a hopelessly paradoxical role. A philanthropist

without a self to give is as much an oxymoron as an impoverished benefactor.

Act I centers on a dinner party during which we see that Philip is surrounded

by people who embody, in varying degrees, Moliere's humanity-hating Alceste.

They include his impatient, passive-aggressive fiancee, Celia, played by Molly

McLain, and the spectacularly boorish blowhard Braham, masterfully rendered

by Ben Elledge. Hampton also introduces some intriguing characters who never

actually appear. They are the students, colleagues and prominent people the

guests take turns sneering at, gossiping about and rendering judgment upon.

In Act II, the focus is narrowed to Philip's relationships with individuals,

chiefly Celia. It is to her that he confesses that, while he likes people well

enough, the driving force in his life is his fear of offending. Philip is more

Pee-Wee Herman than Mother Teresa, which leaves the audience without a central

character to which to react.

Presented with this conundrum, director Rachel Katz Carey has made Philip not

lover, not hater, not fearer. In fact, he's nothing -- alternately an amiable

dishrag and such a naif as to seem dull-witted.

The entire play takes place in Philip's quarters at the university, charmingly

represented by Jeffrey Johnson's set design, which evidences the same attention

to detail as all other aspects of the production: Carey's blocking and stage

business; Stacy Mittag's costumes and Kate Ufema's dialect coaching -- the British

accents sound authentic and, more importantly, are consistent and never impede

intelligibility.

Mark Harvey's lighting design is especially enhancing to several scenes -- and

to the creatively handled scene changes.