C. Step-by-Step Example

In the example below, we will explore various techniques to develop material sufficient to compose a piece in binary form. Remember, as composers we usually cannot only rely on raw inspiration to sustain an entire work. We can, however, draw on a multitude of established methods to transform musical materials. Part of our goal is to create while maintaining an organic unity throughout our work. As such, the techniques we will learn should allow us to write more extensively with only a minimum of original material. When we apply these methods artistically, they can themselves inspire new ideas rather than simply provide a mechanism with which to manipulate them. One mark of a strong composer is the ability to create something unique and emotionally satisfying by using traditional, and perhaps even conventional methods in novel ways.

Techniques and ideas explored in this example include:

Motivic fragmentation/liquidation

Continuity of rhythmic impulse

Melodic inversion

Imitation

Textural changes

Voice exchange

Modulation

Golden Section

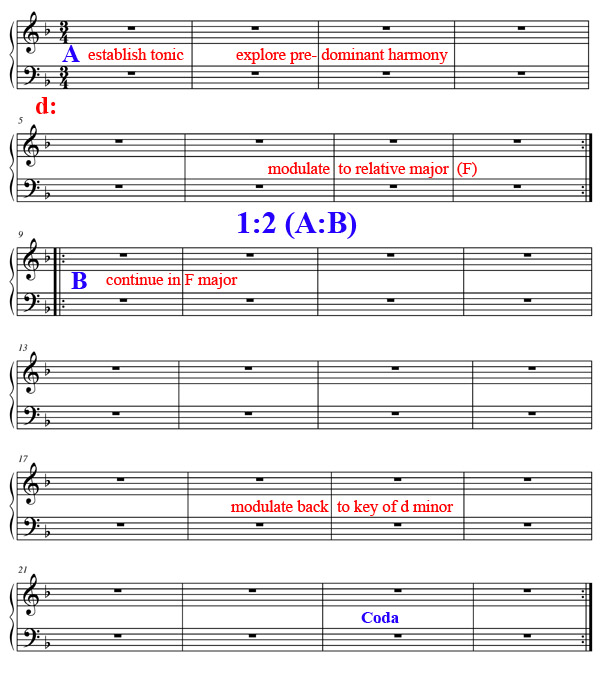

Understanding climax notes1. Outline. To compose a binary form piece ourselves, we need to begin with an overall sense of the structure of the piece, both in terms of the length of each section and the harmonic regions we will be working in. For our piece, we have decided to make the B section twice as long as the A section and tack on a brief coda (or closing section) at the end. Next, we determined the key and meter (d minor and 3/4 time). Without going into too much detail, we can sketch in some harmonic ideas and approximately when they will occur.

2. Motive. Next we need to generate some initial musical material with which to create. We can begin with a motive, which is a compact musical idea that has a distinct profile so that the listener can distinguished it as it is developed throughout the composition. A motive normally consists of a rhythmic idea, a melodic idea, or a combination of both. It's repetition and modification over the course of the piece will provide the listener with a musical element with which to identify with, similar to how we follow a character in a play that goes through some kind of drama and ultimate transformation.

a. Here we have established a bar-long rhythmic motive.

b. Next, we have spun a little melody around this rhythmic idea to best establish our home key of d minor.

c. Finally we can harmonize the motive and complete the first bar. Note that we have engaged three layers of different kinds of activity. Transferring the rhythmic impulse from voice to voice (as we can observe between beats one and two, from the soprano to the alto voice) is crucial to sustain continuity and momentum, which is at the root of this style of composition.

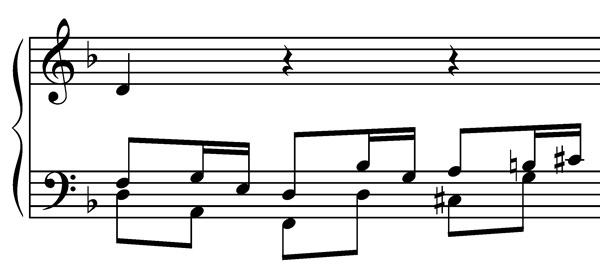

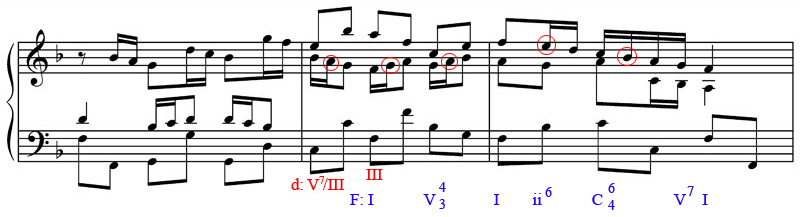

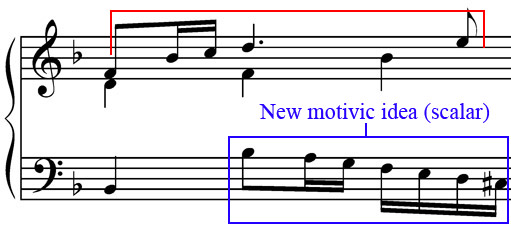

3. Motivic development. In bar 2 the rhythmic dimension of the motive is maintained in the soprano while the contour of the melody is changed. However this will not disturb the continuity with the first bar but will reinforce for the listener the relevance of the rhythmic design as being main material. Note as well we have redistributed the activity between the lower two voices: the alto progresses in broader quarter notes as the bass did in bar one, while the bass introduces a new motivic idea based on a descending scalar pattern and picks up the rhythmic impulse for the second half of the bar.

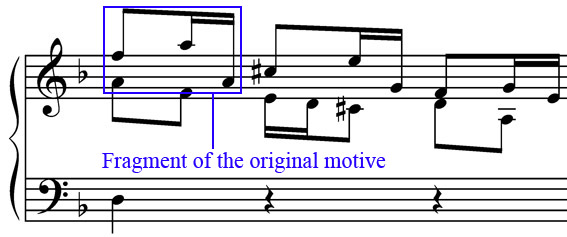

4. Textural Change. In order to bring variety to the texture in bar 3, we can drop out one voice and have a duet between two chosen parts (in this case the soprano and alto). In addition, to avoid needless repetition of the main motive in its entirety, we can take a portion of it and use that as the basis for development. This process, known as fragmentation, can substantially increase the sense of motion in the work. A related technique, liquidation (coined by the 20th century composer Arnold Schoenberg), progressively eliminates portions of a motive and further compresses the rate at which material needs to be processed by the listener.

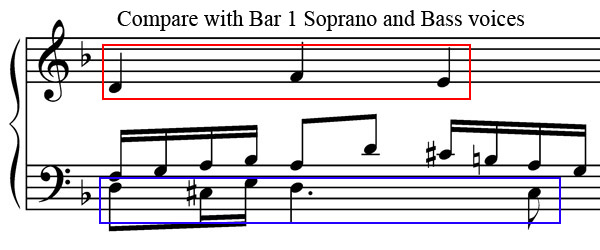

5. Voice exchange. One often-overlooked aspect of composition is the rate at which the attentive listener needs to process musical information as it is manipulated and developed while new material is introduced. At certain points in a piece the listener needs what can best be thought of as moments of relaxation - when the music continues to push forward yet does not do so in a mentally taxing way. One technique to accomplish this is using a voice exchange. Here the composer reuses previously heard music with little or no alteration and simply rotates which voice articulates the earlier passages. In bar 4 of our piece we have taken the main motive from the soprano and dropped it into the bass voice and vice versa.