Rhythmic Composition. Here we will concentrate on exploring 12-tone composition utilizing primarily the polyphonic topography approach set in a bagatelle (a brief piece, usually of a capricious character). To elucidate the manner in which this method of implementing a dodecaphonic matrix can involve a multiplicity of row transformations simultaneously, we will write a chamber piece for winds and piano. In such a concise piece as this, the composition will concentrate on the interplay between just a handful of motifs and textural ideas.

Working with a series instead of a scale sometimes necessitates the composer concentrate on handling leaps rather than steps. As such, it is important to carefully gauge how to use large and dramatic leaps so that the ear of the listener does not tire. The same principles of how we hear a narrative in music apply as it does in traditional tonal music, despite the fact that the materials may be quite different. Composers of the Second Viennese School, including the aforementioned Arnold Schönberg and his pupil Anton Webern (1883-1945), initially borrowed forms from the Classical era for their nascent 12-tone ideas. This lent both composer and listener some familiar ground in which the new musical vocabulary could maturate.

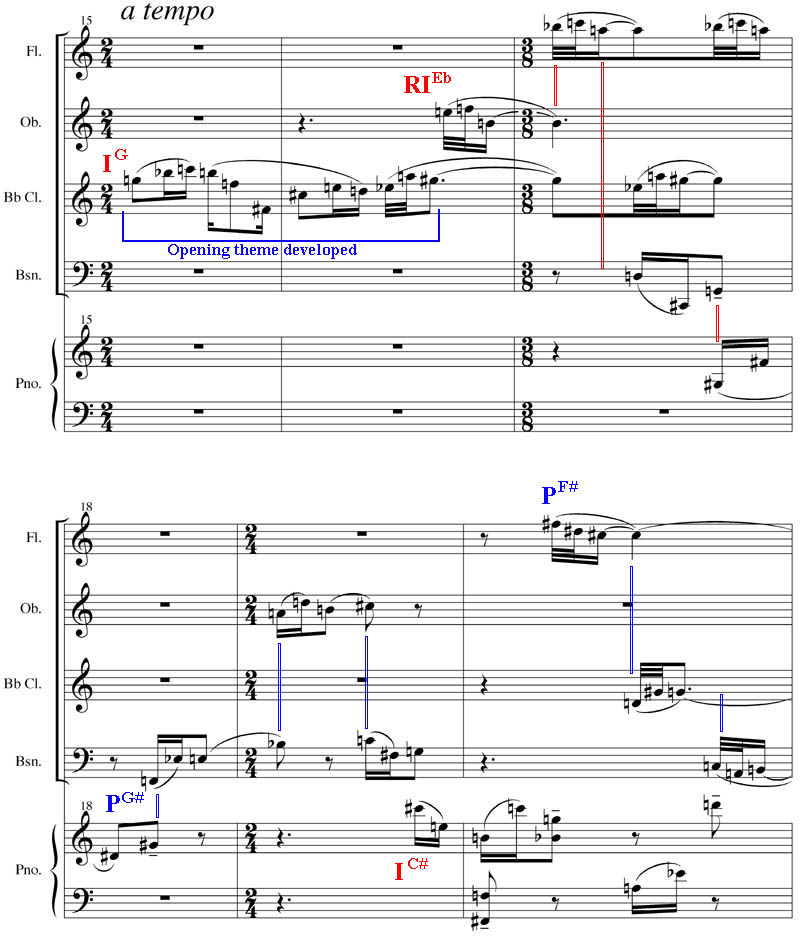

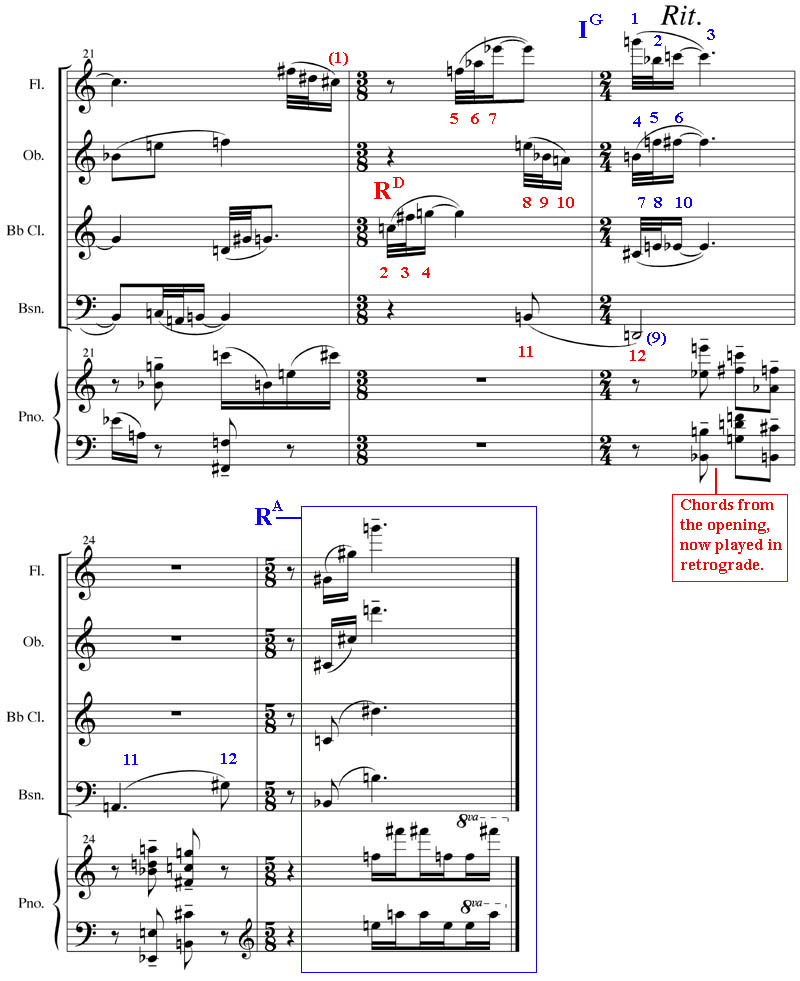

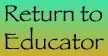

As Webern's particular style evolved, he often sought to apply symmetrical patterns to his musical ideas. This provides a key element to aid the listener in comprehension and also reflects the fundamental serial principle of retrogradable transformation. In a manner, Webern is telling us how to listen to this kind of music through a careful manipulation of the materials to incorporate basic 12-tone procedures into their inherent structures. We have endeavored to apply this concept, albeit sparingly, as in bars 5-7 (and again similarly in 19-21) wherein the piano articulates a pattern that is performed symmetrically.

A contrapuntal section based on interlacing imitative rhythms begins at bar 10 and concludes with a quasi-cadence at bar 14. The ensemble here contrasts the previous polyphonic web with a large 'unison' downward leap with all parts derived from one row. Note that this distinct idea is used at the end of the piece with a final upward leap in all of the parts. These are the only instances of pure block topography in the piece.

Regarding how faithful we remain to the series precise, once again, we find occasions when there needs to be some degree of flexibility for our expressive requirements: in bar 4, the 9th note of the row that is being shared by the winds is skipped, while the final pitch in the piano is eliminated. The composition student must learn to always trust his/her musical instinct even if the system of choice prescribes something else.

Notes on Analysis:

1. The clarinet in Bb sounds as notated (for ease of reading).

2. Unlike the first piece, we have not analyzed every note but rather concentrated on illustrating significant aspects of the present work.Open the matrix in a new window.

mp3 download

complete score download