Dr. Justin Henry Rubin © 2005

A close cousin to our previously discussed binary structures, ternary forms also have only two parts. In addition to the A section being repeated at the end of B (to complete the three-part ABA organization), here the tonal directions that the A and B sections take are also different. This departure is significant in that whereas in the binary configuration the A section cadences outside the tonic key and the B section picks up this thread and subsequently steers us back to the tonic, in the ternary model, A is closed, coming to a cadence in the tonic both times. As well, binary forms are often comprised of sections of nearly equal length, while ternary allows for more flexibility.

AUDIO and MIDI files can be listened to on this page or downloaded separately here.

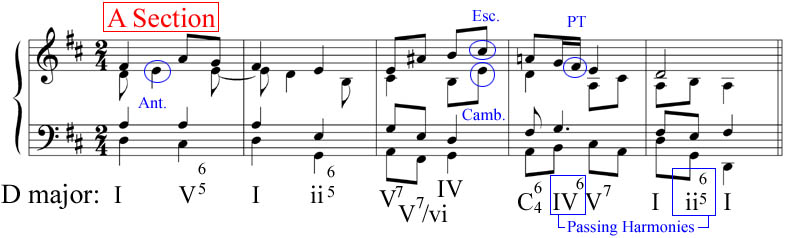

In the following example, we will create a short, lyrical piece for piano in D major.

1. In keeping with the prevailing compositional techniques for the Common Practice, we have begun with a contoured line with a climax about two-thirds through the phrase and a strong cadence in the tonic.

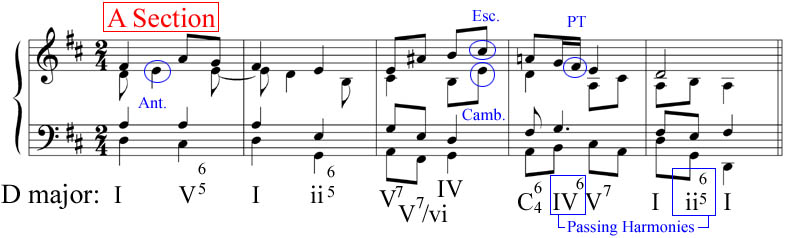

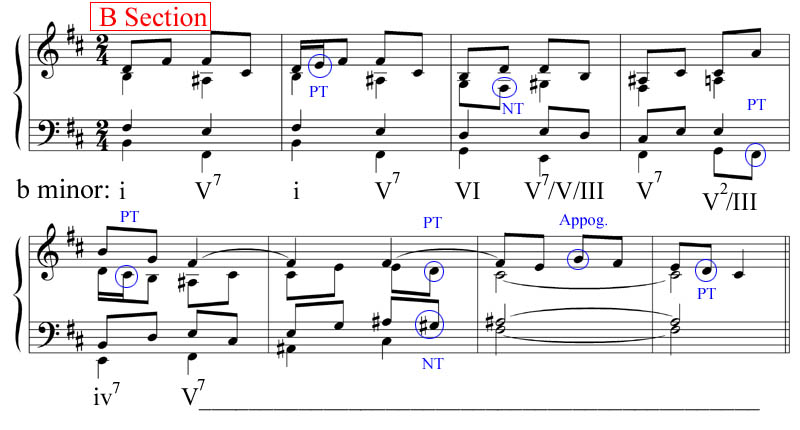

2. Our B section begins with a direct modulation to the relative minor and is nearly twice the length as A. In contrast to A, as well, we have arrived at a cadence in the dominant of the new key making the next direct modulation back to D major even more striking. In the Baroque this section would as often be in the dominant key as the relative one, although by the Classical period the parallel key is observed in the literature. Afterwards, more distant relations became acceptable and even desired.

3. Bringing our three sections together we have completed the requirements of the ternary form. Regarding sectional balance, even in the Baroque we find great variety between the relative durations of parts A and B with the central section sometimes simply consisting of a brief interlude and other times being of a highly developed and expansive nature. In the end, every composer or student composer must for themselves decide what the goal of their music is and what the particular piece needs for proper expression; forms are not shackles to make the author feel constricted, but rather molds, passed down from generation to generation, with which to fill with new ideas and imagination.

mp3 download (piano version)

Continue for an example of a quartal harmony (20th century) adaptation of ternary form.

The views and opinions expressed in this page are strictly those of the page author.

The contents of this page have not been reviewed or approved by the University of Minnesota.

View Privacy StatementCopyright © 2005 by Justin Henry Rubin

http:// www.d.umn.edu /~jrubin1The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer.