BY TOM SKELTON

courtesy of

Dance Magazine

first published

February 1956

TOOLS OF LIGHTING DESIGN: ANGLE AND INTENSITY

The second major factor in lighting design is angle. Angle is determined by where the spotlight is hung and how it is focused. Dance lighting does not have to be content with the45 degree angle the “Cross-Spotting” system provides, since the dance stage usually offers unlimited hanging positions and is not impeded by scenery of ceilings and walls.

As you examine the illustrations keep in mind the fact that without highlights and shadows, form is eliminated, and without form the effect of visibility is eliminated. Remember, too, that individually each angle has its advantages and disadvantages. The problem is that of choosing angles for the chief lighting sources that will give the most form (and visibility) and still be varied enough to be a design element in any specific dance.

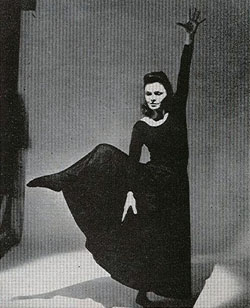

#1 Low Front |

#2 Medium Front |

#3 High Front |

Low Front (#1) from the footlights will make all sorts of shadows, but makes the dancer seem taller. Useful for distortion or unnatural effects since low front lighting does not exist in nature. Spotlights located in the footlight position can make gigantic shadows on the backdrop, which in some cases is useful but in other cases is more interesting than the dancer. |

Medium Front (#2) from a balcony rail at about head level will provide the best shadowless wash-lighting, but bad shadows on the backdrop unless black draperies are used. Especially useful for broad comedy if black draperies are available since it etches the body very sharply. | High Front (#3) will hit the dancer full face, making a chin shadow and eye-socket shadow. Most useful when used dimly to fill in shadow’s produced by other spotlights, or as a follow spot. |

#4 Low Side |

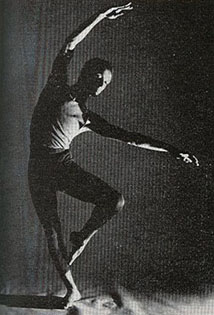

#5 Medium Side |

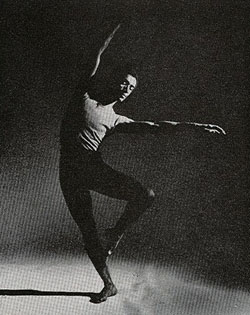

#6 High Side #6 High Side |

Low Side (#4) from spotlights on the floor in the wings is useful primarily to imply the presence of a force off-stage, with less distortion and shadow projections than low front. Difficult to focus properly to cover the moving dancer’s whole body both at center and near the light source, unless the spotlight can be placed on the floor about 10 feet offstage. |

Medium Side (#5) from a spotlight at head level mounted on a standard in the wings. Excellent for giving form to the body, but in group dances it will make one dancer cast a bad shadow on another dancer, and if too close to the edge of the stage it will make a nearby dancer disproportionately bright. (The illumination output of a spotlight falls off very quickly for the first 5 feet, then very gradually; so the medium side spotlight should be 5 to 10 feet off stage.) Focus carefully to prevent spill on sky drop. Weight it firmly so that it is not easily knocked out of focus by a passing dancer. Shoot any dancer who uses the standard as a barre for warm-up (then send me your name and address and your citation will be forwarded immediately.) |

High Side (#6) from spotlight hung 15 or 20 feet above the stage floor focused diagonally down to the stage floor. Gives a tremendous feeling of space. The best angle for transforming a dirty theatre into a magical area. But one spotlight alone cannot cover the whole width (“plane”) of the stage since it would be down lighting to the side nearest the spotlight unless a second spotlight is used to crate the proper angle. |

|

|

Down Lights (#7) which are hung directly overhead and focused straight down are very effective for isolating a single area on the stage, but is a much over-used effect in dance lighting. Gives good dimension to the body but its values are limited for illumination purposes since it lights only the top of the body. Makes the dancer look as though he is being pushed down in a well or under water; but if the dancer lifts his face so that the light catches it he will be pulled up as though a ray from heaven is lifting him. If down-lights are to be used extensively in a ballet or as an illumination source, the choreographer must plan the movement accordingly because of the sudden change of effect that will occur merely by lifting the face. |

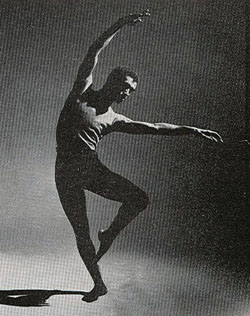

Back Lighting (#8) from spotlights overhead and behind the dancer. Provides very little illumination, but produces excellent highlights. If the color is a compliment of the color used in the front lighting, the body will have a halo. |

Photos of Mary Anthony and Louis McKenzie by Peter Basch

These are examples of light source from a given angle: combinations of these for good dance lighting will appear in the March issue.

Other angles can be produced by various combinations of these mounting positions, combinations of these mounting positions, and the effect will then be a combination. Side-back lighting, for example, will not give a halo, but will provide relatively more illumination and will add height to the stage.

Great emphasis can be obtained by suddenly changing the angle of illumination, in much the same way that a sudden color change can be used. A slow change of angle over a period of time can be a very subtle choreographic element. A ballet might begin with front lighting, reach down lighting for the climax, and progress to back lighting for the final denouement. A ballet that covers a time period might begin with morning-sun amber from a medium side angle, progress to amber down lights, and end with a setting-sun on the other side. A ballet containing interior and exterior sequences could use side lighting for the exterior to imply the sun and down lighting (with dim front lighting added for visibility) to imply overhead lighting fixtures. For Doris Humphrey’s Ruins and Visions, I began each scene with backlighting in a highly theatrical color on the point of interest, sneaking in other lights for visibility after the scene had started; the angle of backlighting announced that a new scene was beginning, and the mood of the scene was set with the color.

If all of the angles are used simultaneously each in a different color, the dancer becomes jewel-like, and has maximum intensity but more form than white footlights alone would give.

Before we apply this discussion of angle to an analysis of the “basic 15 spotlights for dance” (illustrated in Part III, in the December issue) I think we should discuss the 3rd major tool of lighting design: intensity.

INTENSITY

Perhaps the best way to judge intensity is to look at the eyes; if the eyes are bright enough the rest of the body is probably bright enough. The eyes are rarely a choreographic element, so it would seem unfair to flood the body with light just to keep the eyes bright; furthermore, by lighting for the eyes you are encouraging the audience to continue its eye-watching practice (learned from movies and drama) to such an extent that important movement from another part of the body may be missed entirely. This makes for a dilemma, but until such time as a really dance-conscious audience is in the majority I think it best to light for the eyes rather than permit the audience to feel gypped because they see only the body. Designers who underlight the eyes are usually sharply criticized.

Intensity, like color and angle, is a problem of contrast. With dark draperies, little actual intensity is required to create the effect of visibility. With light gray or beige draperies (the most common colors in civic and high school auditoriums) there is so little contrast value, that great intensity is necessary for visibility.

To light Negro skin is primarily a problem of contrast in intensity rather than contrast in color, since the same colors of light are flattering to both Negro and Caucasian skin. The Negro dancer must be especially careful of the color of his costume since in a light-colored costume the intensity required to light the face adequately will simultaneously make the costume so bright that more light is necessary for the face which in turn will make the costume too bright, and so on. It is wiser to choose a dark costume that will not offer too much contrast to the skin.

Most lighting designers always keep the intensity a little less than full because that extra 5% makes a difference between brightness and harshness. Others prefer to save the 5% until a slight increase of intensity can best be used to relieve the monotony of a long climax-less section or until the climax itself. When you are working with a less-than-adequate amount of equipment, it is often necessary to use full intensity simply to attain visibility; but once visibility has been established a very slow dim will not be noticed by the audience and will not affect the visibility if it is slow enough to permit the pupils to adjust naturally. You then have the little extra light to use later in the ballet.

Variety is as necessary with intensity as it is with color and angle. How monotonous is a whole evening of ballets with the same intensity. Alternating black draperies with a sky drop is the simplest way to get variety, but it is not always possible because of the programming, or drapery availability.

In summary, the three tools of lighting design – color, angle, and intensity – must always be used with variety and contrast uppermost in the designer’s mind. If any one element is changed, emphasis results – and that can be as dangerous as it may be helpful, unless it is used with the utmost care.

Article VI will combine these elements to show how they may be used for good dance lighting. Article VII will deal with standard commercial lighting equipment and will offer a few suggestions on how to improvise lighting equipment from “scotch tape to chewing gum.”

THE END