In mid-November 1872 during intensely cold snow storms at the summit of the Sierra Nevada near Donner Pass, an aspiring landscape painter from Connecticut sketched along side one of the nation's most illustrious artists. "I am now sketching this place with [Albert] Bierstadt (1830-1902)," wrote Gilbert Munger. "We work from sunrise to sunset, muffled up to our eyebrows in furs ... We are sketching in the snow, sketching snow-storms and snow effects ... I am now familiar with the scenery and know where all the best things are."[1] He went on to relate that Bierstadt "wishes me to accompany him on his sketching tours," but while they stayed in contact over the next five years[2] Munger and Bierstadt apparently did not sketch together again.

While today we know much about Albert Bierstadt, Munger's name and artistic achievements have been generally forgotten until recently. In his day he was a highly regarded painter in New York, San Francisco, and London. He socialized with leading scientists and artists. But like many artists of his generation he went largely unnoticed in the twentieth century. His rediscovery by scholars and collectors is a story in which the Internet has played an important part.

Munger began his artistic career in his early teens as an apprentice engraver in Washington, D.C., before the Civil War. He was soon engraving large plates of landscape views and scientific specimens for federal government reports of exploring expeditions[3] Talent and determination gained him entrance to a circle of explorers, geologists, cartographers, and writers associated with the survey expeditions of the American West. After the war, Munger's first success as a painter, like Bierstadt's, resulted from his production of dramatic images of sites popular with tourists. In the East he tried his hand at painting Niagara Falls, but it was in the Far West, particularly in California, that he gained recognition as one of the nation's most promising artist-explorers.

Munger first traveled west in June 1869 with the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, headed by the charismatic young geologist Clarence King (1842-1901). Working beside landscape photographers Timothy O'Sullivan (1840-1882) and Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916), Munger accurately depicted the topography and geology of little known regions for survey geologists. Munger's western paintings also evoked the poetic sentiments demanded by art connoisseurs schooled in the aesthetic conventions of the Hudson River school. One critic praised both aspects of his work, writing: "He has a conscientious feeling for Nature, and enough poetry to temper the harshness of the real with the softness of the ideal."[4] But another critic suggested that the scientists were the more demanding audience: "It is a further proof of his fidelity to nature that Prof. [Josiah Dwight] Whitney (1819-1896) and several other scientific men here have given him commissions."[5] "Poor Munger!" the writer went on, "We would rather paint for the most exacting connoisseurs than for scientists."

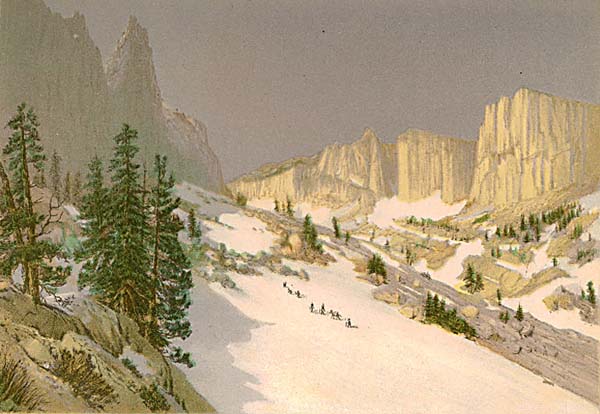

| Plate II: Lake Marian, Humboldt Range, Nevada, by Munger, 1871. Signed and dated "Gilbert Munger 1871" at lower right. Oil on canvas,26 by 44 inches. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Daniel A. Pollack; photograph courtesy of North Point Gallery. |

|

Lake Marian, Humboldt Range, Nevada (Plate II) is a fine example of Munger's work of this period. Both Munger and King were inspired by the visual drama of this perfectly symmetrical alpine lake, which King described as a "Giant's Bowl" carved from the earth's oldest, hardest rock by glaciers.[6] Munger painted at least four versions of the scene. One was loaned to Yale College (now University) in New Haven, Connecticut, where it was shown to geology students. Another was acquired by King, an art connoisseur and avid collector as well as a scientist and writer. Munger was especially fortunate to become friends with King, who for many years provided him with access to the worlds of science and art. Munger did the illustrations for King's magnum opus, Systematic Geology,[7] volume one of the government-published record of the fortieth parallel survey. The ten chromolithographs produced from his oil sketches, such as Summits - Wahsatch Range - Utah (Plate III), are compelling images of western exploration of the 1870s.

|

Plate III: Summits - Wasatch Range - Utah, by Julius Bien (1826-1909), after a painting by Munger. Chromolithograph, 6 by 8 inches in Clarence King, Systematic Geology (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1878), between pp. 44 and 45. |

| Plate IV: Along the Monterey Peninsula, by Munger, 1873. Signed and dated "Gilbert Munger 1873" at lower right. Oil on canvas, 13 1/2 by 23 inches. Private collection; photograph by courtesy of A. J. Kollar Fine Paintings. |

|

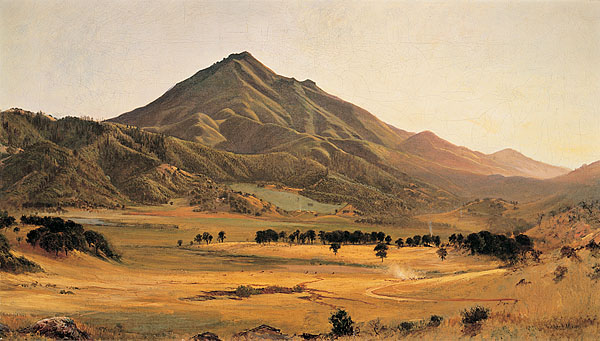

At the end of this first season with the survey, Munger arrived in San

Francisco on October 31, 1869, and quickly rose to the top of the

hurly-burly art market there. He painted the scenery around the Golden

Gate from Monterey Bay to Marin County. Along the Monterey Peninsula

(Plate IV) demonstrates that his mastery of luminous effects of sea

and sky was highly developed. The composition shows Carmel Bay with

Point Lobos in the distance at the left. (Today you might see Tiger

Woods playing golf along this stretch of seashore.) His work was praised

in the San Francisco press. Of Mount Tamalpais from San Rafael

(Plate V) one critic wrote, "If we wanted to send a sample chip' of

California ... we might send this picture with complete confidence and

satisfaction."[8]

|

Plate V: Mount Tamalpais from San Rafael, by Munger, c. 1870. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower right. Oil on canvas, 19 1/2 by 33 1/2 inches. Private collection; North Point Gallery photograph. |

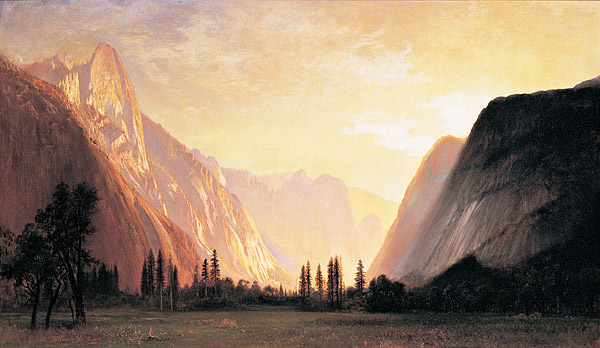

From San Francisco Munger made his first visit to Yosemite in 1870. While he produced many paintings of Yosemite, only one of exhibition scale has been located. Yosemite Valley (Plate VII) provides a dramatic, yet authentic representation of twilight in the Valley, that hour, King declared, when "there is no more splendid contrast of light and shade."[9] Munger's western paintings are often dramatic like Bierstadt's, but do not invent marvels of topography to enhance the drama, as Bierstadt did in several major works.

| Plate VII: Yosemite Valley, by Munger, 1870s. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left. Oil on canvas, 28 by 48 inches. Collection of Nick and Mary Alexander; photograph courtesy of William A. Karges Fine Art. |

|

When the King expedition took to the field again from San Francisco in August of 1870, Munger accompanied them to Mount Shasta and the Pacific Northwest. In November of that year he returned to New York City, but by May 1872 he was traveling west again, this time at his own expense, to paint at Shoshone Falls in Idaho and in California. He returned to New York once again in November 1873 and then embarked on a third trip to sketch Yosemite and the Sierras in the summer of 1875, a trip that lasted through November.

|

Plate VI: Bridal Veil Falls. Yosemite Valley, by Munger, 1877. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left and inscribed "Bridal Veil Falls. Yosemite Valley. Gilbert Munger 1877" on the reverse. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 by 28 1/2 inches. A detail appears on the [magazine] cover. Private collection. |

While in New York between trips Munger filled orders for paintings of western scenery based on his oil sketches. As an example, Bridal Veil Falls, Yosemite Valley (Plate VI) is a picture that a geologist, tourist, or art connoisseur could admire, with its clarifying light and precise topographical detail. He also spent time in Saint Paul and Duluth, Minnesota, where his artistic talents were pressed into civic service. Duluth (Plate VIII) was commissioned to promote a proposed Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad and to show the newly accessible harbor at the western extreme of the Great Lakes. The scene carries our gaze across a panoramic expanse of Lake Superior to a distant horizon revealing the earth's curvature against a luminous sky.

| Plate VIII: Duluth, by Munger, 1871. Signed and dated "Gilbert Munger 1871" at lower left. Oil on canvas, 25 by 50 inches. Collection of the City of Duluth, Duluth Public Library, Minnesota. |

|

Munger's paintings of western subjects were making an impression back east. In 1872 a critic in Washington, D.C., commented: "It must gratify Mr. Munger's old friends here to know that he is rapidly and surely taking his place in the front rank of American artists."[10] By the time of the United States centennial, Munger was nationally recognized as a gifted landscape painter.

In 1877 artistic ambition led him to go to England to search for new styles and international artistic distinction. Perhaps noticing that he had already profited handsomely from sales to English tourists in the United States, he set up a studio in London, where he quickly became a successful painter and etcher working among the cosmopolitan expatriates. Asked later the reason he moved to Europe, Munger replied: "It is the sure means of growth in art everywhere at hand in these old lands."[11] Reflecting years later, he wrote:

"After exhausting my American studies I changed my method completely, and went to work painting the natural scenery of England and France, changing from mountains, bluffs and rugged natural scenes, such as I had been handling, to the soft, mellow and reposeful scenes of the countries named."[12]

Talent and hard work provided success in a highly competitive field of artists. Munger quickly enjoyed patronage and professional recognition in England, where he was befriended by John Everett Millais (1829-1896). He sketched in Scotland with Millais, who invited the young American to "swell entertainments" at his grand studio in London.[13] "Millais is now one of my best friends in London and has more influence than any other artist here," Munger wrote to geologist Samuel Franklin Emmons (1841-1911) in 1877, adding that he had dined in Paris with Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904), the African explorer, and in London with Heinrich Schleimann (1822-1890), the German archaeologist, who, Munger wrote, "has been digging up Troy and expects to dig up the rest of the world before he gets through."[14]

|

Plate IX: San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, by Munger, c. 1882. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left. Oil on canvas, 20 by 30 inches. Collection of Alice Jamar Kapla. |

John Ruskin (1819-1900) encouraged Munger to paint Venice, which he did on a trip there in 1882.[15] A dozen of the Venetian paintings were shown at the Fine Arts Society in London upon his return in November, including probably San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice (Plate IX). Munger's selection of subjects reflected the ideas of Ruskin and Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) of a cultural tourist's pilgrimage. In most of his paintings of Venice Munger carefully excluded all signs of the modern age.

| Figure 1: Gilbert Munger (1837-1903) in a photograph taken c. 1890, used as the frontispiece of [James Cresap Sprigg] Memoir: Gilbert Munger: Landscape Artist, 1836 [sic] - 1903 (De Vinne Press, New York, 1904). |

|

Entirely self-supporting from his artistic production, Munger sold through fashionable London art dealers as well as directly to collectors. His paintings were hung on the line at the Royal Academy there and were favorably reviewed. He even wrote a play that was produced at the Haymarket Theater in 1886. Monarchs and museums bestowed honors on him (see Figure 1). In keeping with the custom of successful professional artists in London in the 1880s, he dressed as a gentleman and maintained an impressive studio near New Bond Street in the most fashionable district, where old friends from America found him "in a most prosperous condition."[16]

|

Figure 2: The Herring Fleet, by Munger, 1879. Signed "Gilbert Munger" outside of plate, at right. Etching, 7 by 11 inches. Private collection. |

Munger also returned to producing prints in London. One reviewer noted: "The Burlington Fine Arts Society has taken Mr. Munger up and he is now overwhelmed with orders for etchings. ... The etchings are sold at high prices, yet secure a very large sale."[17] Few examples of Munger's etchings currently are known, among them a simple landscape and The Herring Fleet (Figure 2), but press reports of the time suggest that additional examples will be discovered as the artist's name becomes better known.[18]

| Plate XIII: French Forest Scene, by Munger, c. 1890. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left. Oil on canvas, 32 by 25 1/2 inches. Tweed Museum of Art, Orcutt family gift in memory of Robert S. Orcutt. (Plate I in original article shows a detail from this painting.) |

|

In London Munger's paintings became increasingly poetic and nostalgic following the trend toward the Barbizon style, although he never wavered from his commitment to painting on the spot - en plein air. During his European period his primary market remained in London, but Munger found England damp and cloudy, so in 1886 he moved to France where he worked mostly around Paris. The forest preserve of Fontainebleau, just a short train ride away, was a favorite subject of Barbizon artists and a popular destination for tourists. Munger's depiction of ancient trees in French Forest Scene (Plates I, XIII) presents with a clarity reminiscent of his earlier American works a brightly lit, detailed portrait of a great tree, within a typical Barbizon composition. In Seine Near Poissy (Plate XI), another Barbizon example, a row of imposing trees is suspended in a luminous surround of water and air. These effects of light are not common in Barbizon painting and also reflect Munger's American experience. The small house boat tied to the river's edge is probably Munger's field studio, an arrangement he adopted in Europe in order to maximize his painting time out of doors. He first used a field studio in Scotland in 1877, where he managed to keep painting despite the "drenching rain" by working inside a seven foot square collapsible wooden box with a picture window, which he hauled around by wagon to picturesque locations.[19] Later on the Thames River he used a "miniature Noah's ark" in which he completed large canvases, "painting in rain or shine."[20]

|

Plate XI: Seine near Poissy, by Munger, c. 1890. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left. Oil on wood, 15 by 21 1/2 inches. This paintings was reproduced as a plate in [Sprigg], Memoir, between pp. 12 and 13. Private collection. |

Reflections on a Lake (Plate X), represents Munger's fully developed Barbizon style. Gone is the focus on a particular element, such as a tree, although the entire scene is rendered with a level of detail seldom seen in Barbizon paintings of others. Typically in Munger's later Barbizon pictures, country folk and animals are glimpsed beside placid rivers or ponds, or in sunlit clearings of the stately forests. For late nineteenth-century viewers, such scenes muted the unsettling displacement of nature by modern life. Munger, with his background in the service of geology and science, was well suited to frame these perceptions within his own use of the Barbizon aesthetic conventions. Critics approved of Munger's contributions to the style. The London Daily Telegraph remarked:

"Rub out the signature of Gilbert Munger ... from any one of his landscapes, and it would pass for a work of that same school which glorifies the forest scenery of Fontainebleau. Corot, in his deeper and firmer moods, is reproduced, with no slavish effect of dull mechanical imitation, but with appreciative reverence of an original hand by this same Mr. Munger."[21]

| Plate X: Reflections on a Lake, by Munger, c. 1890. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower right. Oil on mahogany, 12 by 18 inches. Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota Duluth, gift of the Orcutt family in memory of Robert S Orcutt. |

|

Munger returned to the United States in April 1893. Attempting to resume the American career he had left more than sixteen years earlier, he hoped to capitalize on his European reputation and honors. But his connections with the American art market had grown stale. Buyers for his paintings were hard to find and critics largely ignored him. He never regained the recognition he once enjoyed nor achieved the financial success he wanted. Near the end of his career he wrote sardonically, "It will not be my fate to become a millionaire (this misfortune has come to many of my friends)."[22]

|

Plate XII: Cazenovia Corn Field, by Munger, c. 1900. Signed "Gilbert Munger" at lower left. Oil on canvas, 34 by 58 inches. Tweed Museum of Art, gift of Melville Silvey. |

In this last phase of his career, despite financial adversity and illness, his paintings achieved a new weight and concentration of emotion, further refining the lessons of Europe. Cazenovia Corn Field (Plates XII), painted around 1900 while visiting artist friend Dwight Williams (1856-1932) in upstate New York, shows this more expressive style, producing his own compelling vision of a rural American Barbizon.

Munger's early works are painted in the crisp realistic style of the Hudson River school; his later European pictures blend an American sensibility with the aestheticism of Turner and the French Barbizon style. Through his long career Munger's perception of nature deepened and matured, but he always remained true to his commitment forged in the open air of the American West to painting finished pictures on the spot. Critics acknowledged that his finest paintings equaled the work of leading artists of his generation, such as Bierstadt. Later he was compared with Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867) and artists associated with the Barbizon school. Most compelling to many viewers today are his earlier western landscapes. Their clarity, geological specificity, and poetry are a remarkable record of exploration and first encounter that communicates Munger's sense of wonder and beauty in the landscape, placing them among the major achievements of the nation's artist-explorers in the 1870s.

It was not until 1982 that the first contemporary studies of Munger

appeared.[23]

Since then much new documentation, along with many previously unlocated

paintings, etchings, and photographs have been uncovered in preparing a

Web site devoted to the man and his art.[24]

The site presents the full text of period records and commentary

concerning the artist, along with images of almost all known works. The

Web site has catalyzed collaboration among scholars, curators,

collectors, conservators, and art dealers in renewing appreciation for

Munger's place in American art history. Today Munger's oeuvre numbers

over two hundred works dating from 1853 to 1902. We suspect that many

remain to be discovered.

To commemorate the centennial of Munger's death in 2003 the Tweed Museum of Art at the University of Minnesota Duluth, the holder of the largest collection of the artist's work, has prepared a major traveling exhibition supported by a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation in New York City and the Alice Tweed Touhy Foundation in Santa Barbara, California. The show will open at the Tweed Museum on July 26 and will be on view there until October 12. Future showings will be listed in Calendar. The exhibition is accompanied by Gilbert Munger: Quest for Distinction, written by Michael D. Schroeder and J. Gray Sweeney. and published by Afton Historical Society Press, Afton, Minnesota.

J. Gray Sweeney, a professor of American art history at Arizona State University in Tempe, writes extensively on American art.

Michael Schroeder is assistant director of Microsoft Research Silicon Valley in Mt. View, California, and created the Munger website.

[1] Gilbert Munger, "Summit Sierra Nevadas," to his brother Russell Munger, November 7, 1872; reprinted in the St. Paul [Minnesota] Daily Pioneer, November 15, 1872.

[2] An entry for March 20, 1875, diary of Samuel Franklin Emmons (Emmons papers, manuscript division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.) states that he and Munger dined with the Bierstadts in New York City.

[3] "Our Portraits: Gilbert Munger," in [Coburn's] New Monthly Magazine [London], new ser., vol. 2, no. 117 (June 1880), p. 658.

[4] San Francisco Alta California, March 27, 1870, p. 2; clipping courtesy of Alfred Harrison

[5] San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser, November 15, 1873, p. 5; clipping courtesy of Alfred Harrison.

[6] Clarence King, The Three Lakes: Marian, Lall & Jan, and How They Were Named (privately printed, 1870); reprinted in Francis P. Farquhar, "An Introduction to Clarence King's The Three Lakes," in Sierra Club Bulletin, vol. 24, no. 3 (June 1939), p. 109.

[7] Clarence King, Systematic Geology (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1878).

[8] Alta California, August 28, 1870, p. 1.

[9] Clarence King, Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada (Boston, 1872), p. 144.

[10] Washington D.C. Evening Star, November 27, 1872, p. 1; clipping courtesy of Merl Moore.

[11] Cited in [James Cresap Sprigg], Memoir: Gilbert Munger: Landscape Artist, 1836 [sic] -1903 (De Vinne Press, New York, 1904), p. 18.

[12] Saint Paul Dispatch, June 3, 1893, p. 5.

[13] Munger, London, letter to Samuel Franklin Emmons, written from London, Christmas Day, 1877 (Emmons papers).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Munger, Venice, to friends in Saint Paul, September 7, 1882, printed in the Saint Paul Pioneer Press, October 22, 1882.

[16] Walter Paris to Myra Dowd Monroe, reported in Myra Dowd Monroe, "Gilbert Munger, Artist - 1836 [sic] -1903," a paper given at the Madison Historical Society, Madison, Connecticut, published in Madison's Heritage, ed. Philip S. Platt (Madison Historical Society, Madison, Connecticut, 1964) p. 122.

[17] Boston Evening Transcript, June 20, 1879, p. 3; clipping courtesy of Alfred Harrison.

[18] Indeed, just before press time, four etchings of London scenes were located at the Harvard University Law Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts. They have not yet been inspected by the authors.

[19] Munger to Emmons, Christmas Day, 1877.

[20] Saint Paul Pioneer Press, April 24, 1881, p. 5.

[21] London Daily Telegraph, May 15, 1886; quoted in [Sprigg], Memoir, p. 15.

[22] Munger, Saint Paul, to his niece Alice Munger Silvey, June 19, 1893 (Munger family collection).

[23] See J. Gray Sweeney, "Gilbert D. Munger," in American Paintings: Tweed Museum of Art and Gleensheen, the University of Minnesota Duluth (Tweed Museum of Art, Duluth, 1982), pp. 46-69; and Hildegard Cummings, "Gilbert Munger: On the Trail," in Bulletin of the William Benton Museum of Art, no. 10 (University of Connecticut, Storrs, 1982) pp. 3-22.

[24] Michael D. Schroeder, The Paintings of Gilbert Munger: A Catalog of Works and Chronological Document Archive, a Web site hosted by the Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota Duluth, (http://GilbertMunger.org). It first appeared in 1999.