BY TOM SKELTON

courtesy of

Dance Magazine

first published

November 1955

PART II: LIGHTING (Cont’d)

Last month I discussed some of the general problems of dance lighting, the most significant of which is the lack of precedent. Since dance lighting is such an infant, we must study the more mature theatre lighting and profit from its many valuable concepts. It will become clear as we go along that there are basic differences between the lighting needs of actors and those of dancers, but before you can honestly deviate from the accepted approach you must have a basis for understanding it. You must understand what you’re fighting for when your local lighting specialist tries to give you something you don’t want.

Stage lighting, unlike other forms of lighting, is required to conceal more than it reveals, for it must transform the stage area from a rough wooden floor with walls of dirty material into a magic-charged area, and it must transform the puffing, sweating dancer with make-up stained costumes into a magical creature of imagination.

This transformation cannot be accomplished merely by pouring lots of white light into the stage, for the talent of the performer is not enough to transcend sweat and dirt. This transformation can take place only by a very careful use of rays of light, where each element of color, intensity, and angle is carefully worked out and rehearsed, thrown out and tried again, and polished until nothing is left to chance.

The basic purpose of stage lighting, is to permit the performer to be seen by the audience. Less than absolute visibility is permissible only when the effect of the lighting can more powerfully state or emphasize the theme of the choreography – and it is a wise choreographer indeed who knows when, to what extent, and for how long, an effect of lighting can successfully assume the responsibility of creativity.

While white footlights provide plenty of intensity and might seem to be the logical answer, intensity alone does not insure adequate visibility. The performer becomes a bright flat object with an equally bright background; subtleties of expression and color are completely washed out: any attempt at “magic,” at making the stage area a physical or mental place of the imagination, is impossible. Many vaudeville performers find that this bright flatness is desirable, that it helps comedy, where dimension, “magic,” and distortion are of secondary importance. Acrobats, too, require bright flat illumination so that their eyes will not be tricked by shadows and colors.

Thanks to Stanley McCandless and other pioneers in modern stage lighting, we know that the major illumination source should come from above the eye level, say 45 degrees. This will properly illuminate the eye socket, one of the actor’s major tools, and the shadows that are produced are more or less natural and common since the sun and the electric light bulb are usually above eye level and produce the same kind of shadow. To give maximum plasticity to the body, the light source should be 45 degrees to the side. Architects, too, in their renderings have conventionally assumed that the sun’s rays are falling diagonally over one shoulder since this angle provides more plasticity and the best balance of light and shade. The body now has maximum illumination and maximum plasticity, from the one light source.

When the face is turned away from the light source, however, it falls into shadow, so again we draw from nature and discover that when one side of the body is lit by the sun or the light bulb, the other side is not complete shadow since there is reflection from walls, trees, sky, or ground. Since stage draperies and floors do not have the same reflection value, we must add another spotlight on the shadow side. One of the spotlights should be a warm color, as is the sun, the light bulb, or the fire, and the other should be a complimentary cool color, as is reflected light. The two sources should be as widely separated as possible – in nature it’s an angle of 180 degrees, with the sun in front and the major reflected light behind, but since our purpose is visibility for the audience we should put both light sources in front of the actor and separate them preferably by a 90 degree angle. To illustrate these positions further, raise both your arms diagonally forward and upward, and you are pointing at the ideal location for the spotlights.

One side of the body is warm, and the other is cool, and the center of the body is brightest and becomes a third color because it receives light from both sources. If the warm and cool colors used are true complementaries, the third color will be white (in light, when you add two complementaries the result is white.)

This system of two light sources for every area of the stage is called “cross-spotting.” Thanks to the differences in color, highlights and shadows are produced, and therefore we have form or a third dimension. This form, in turn, produces the “effect of visibility,” much more than all of the white footlights in the world.

Visibility can be further heightened by contrast with scenery or draperies. Everyone understands that a red costume will not fare well against a red drapery. For this reason, it is wise to use one set of lighting instruments to light the stage area used by the performer (called the “acting area”), and a different set of instruments to light the background of scenery or draperies.

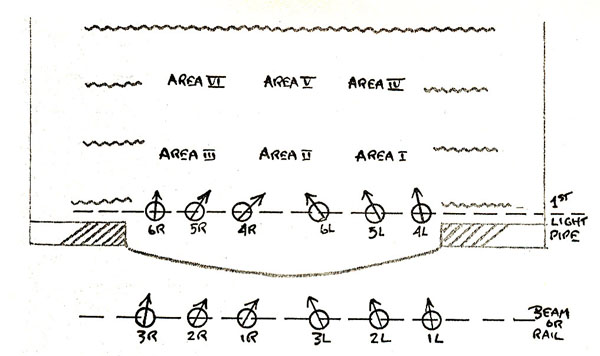

This pretty much covers the approach of the “cross-spotting” technique, in a simplified way at least. Now just a few details on the method. The acting area is usually divided into six imaginary sub-areas (although a larger stage may have nine or twelve, or the setting may eliminate some areas entirely). This means that we will need twelve spotlights to cross-spot the six areas. For convenience the areas are numbered Down Stage Left being Area #1 etc. (if the dimmer board is on stage left). If each area’s spotlights can be controlled separately, the flexibility of the system becomes apparent since any area can be isolated or emphasized simply by changing the dimmer reading.

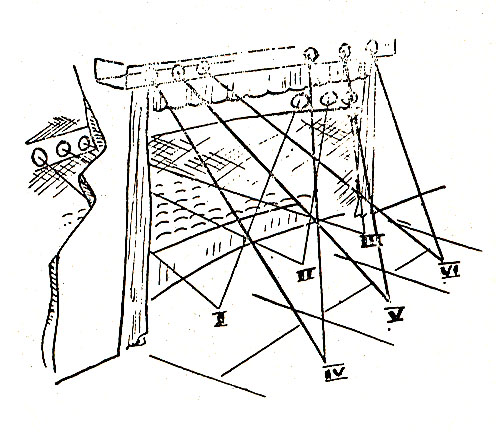

A simplified version of the McCandless “Cross-spot” system in which each of the stage’s six area is lit by two spotlights. The two spotlights which cover each area are as close to a 90 degree angle to each other as possible, and vertically they are 45 degrees above eye-level.

The three downstage areas, Areas #1, #2, and #3 (see illus.) are lit by the six spotlights located in the auditorium ceiling (called “beams”) or mounted on the front of the balcony (called “rail”) whichever comes closest to 45 degrees. The three on the left are in one color, and the three on the right are in the complementary color. The three upstage areas (Areas #4, #5, and #6) are lit by the other six spotlights located on the farthest down-stage overhead pipe or batten (“first light pipe”) duplicating as nearly as possible the angle of the “front” lights.

In addition to the twelve spotlights, footlights and borderlights (in red, blue, and green – the primary colors of light which when mixed will produce any color) are used: 1) to blend the space between “hot spots” (a spot lights brightest spot or focal center) so that as the performer moves across the stage the lighting on him is even; 2) to give color value to shadows that are produced by the “cross-spotting”; 3) to provide a greater color range than the two spotlights alone could have, and to illuminate, when desired, the background. The footlights and borderlights are always used very dimly since their angle would produce quite unnatural distortion if they had to provide actual illumination.

A few extra spotlights will be needed for special effects, to illuminate drops or backings of windows or doors, or give extra illumination to a doorway or chair that requires something special.

This “cross-spotting” system (also called “area-lighting”) is as you can see, a practical method of fabricating a natural effect, and since it derives from nature, its approach is valid. It answers the actor’s primary need, which is to have his face well-lit, assuring form and visibility and a certain amount of both glamour and realism, and it satisfies the director and designer by permitting selectivity for emphasis, mood, or composition.

It is the father of all modern stage lighting concepts, and is used, if only as a stepping-off point, consistently in universities and little theatres. Its practicality is time-proven. Broadway lighting designers have had to deviate considerably from the “cross-spotting” system, however, because old-style architecture of the theatres does not permit mounting the “front” lights in the proper position. Most front lighting has to originate from the balcony-front or “rail,” and in the Broadway theatres this position is only slightly above the head level of the actors. About the best that front lighting can do is wash in some flat illumination which produces bad shadows on the back wall, so the form-giving spotlights must somehow be hung in the stage area.

The primer for modern stage lighting, in which are expounded the theories of “cross-spotting,” is a small readable book by Stanley McCandless of Yale Univ. called A Method of Lighting the Stage, published by Theatre Arts, Inc. You will enjoy reading it, since it goes into much more detail than I have and it will give you an excellent background for communication with your technician who probably considers it his bible.

The requirements of dance lighting do not contradict the “cross-spotting” system, but the emphasis is quite different since in dance we are not concerned with “a face in a place,” but rather with “a moving body in space.” There are three basic differences: 1) Dance uses space in such a different way that the “six acting areas” concept must be replaced with at least twelve dance areas. 2) Lighting must give the dancer a much greater three-dimensional sculpturing than the actor requires. 3) Since dance is a formalized art form it is much less concerned with realism and is more dependent on lighting to help create psychological, as well as physical, places of the mind and body, often in an expressionistic way.

I will elaborate on these differences in detail in the future but for now I want to re-emphasize the technical words introduced in this month’s article, some of which may be new to you, but all of which should become a part of your active stage vocabulary.

Acting area – that part of the stage area that is visible to the audience and used by the performer.

Beams – a mounting position for spotlights in the auditorium ceiling, sometimes called “false beams’ because of a masking piece.

Rail – a pipe or box on the face of the balcony used to mount spotlights, sometimes called “balcony-front.”

Light pipes – pipes suspended over the acting area out of sight of the audience, used as mounting positions for spotlights. These “light pipes” are numbered, starting with the extreme downstage pipe as the “firsts pipe.” The pipes, or “battens” used for borderlights are usually considered separately and are simply called “first borderlight pipe” and “second borderlight pipe” etc.

Hot Spot – a spotlight’s focal center or brightest spot.

(to be continued)