BY TOM SKELTON

courtesy of

Dance Magazine

first published

April 1956

TOOLS OF LIGHTING DESIGN: LIGHTING A JAZZ NUMBER & A BALLET PAS DE DEUX

Unlike Miss Anthony’s current dances, for which we discussed the lighting in the march issue, Louis McKenzie’s Beal Street Lament is a show piece, using jazz movement for mood value. The movement is often big, but always has a feeling of blues, or depression, or lament. The floor pattern for the first section is in the center path, moving upstage and downstage, and the movement focus is front. For the second section, the focus of the movement turns to the side, and the floor pattern takes him from stage right to stage left in the down and center planes. It ends as it began, with Mr. McKenzie in place center stage with the arms spread in an attitude of hopelessness.

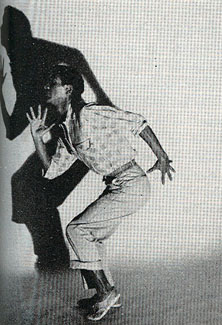

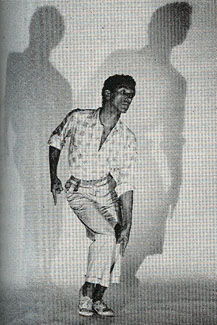

The lighting for this kind of dance can be more frankly theatrical than that of Miss Anthony’s, but the same considerations of visibility, movement focus, body delineation and form must be kept in mind. An interesting device for jazz movement is to project the dancer’s shadow on the backdrop with spotlights placed in front of the footlights. As February’s “angle photographs” illustrated, front lighting washes out the body and doesn’t permit enough highlight and shadow to see the movement clearly; but the shadow projection provides enough interest to justify its use (illus. #1 and #2) providing the effect is not used for so long a period of time that the multi-colored shadows draw all interest away from the dancer.

1 |

2 |

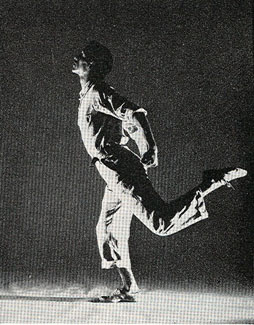

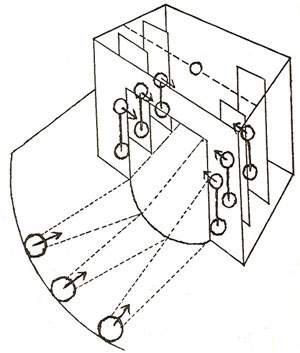

For Beal Street Lament I would begin with this effect, preferably with three spotlights in the primary colors of red, blue and green. For the second section, as the movement focus turns to the side, I would fade out the footlight spotlights and substitute spotlights from the side, also placed on the floor. The movement immediately becomes more interesting and the body more visible, while the low angle provides theatricality consistent with the lighting of the first section (illus. #3 and #4).

3 |

|

Since primary colors were used in the footlight spotlights, I think it would be interesting to use secondary colors for the side spotlights: ambers, blue-greens and magentas. But since Mr. McKenzie ends the dance by returning to the opening pose, I would return to the opening lighting, and blackout on the last note so that the footlight spotlights would not make distracting patterns on the curtain as it closes.

Of the “Basic 15 Spotlights”, this dance uses on 7. The fact that none of them are on standards complicates the procedure slightly since a few minutes are needed to remove the spotlight from the standards and place them on a piece of asbestos on the floor in the wings. The spotlights that are used in the footlights, however, are not included in the ”Basic 15,” but if three extra spotlights are not available the effect could be accomplished in either of two methods: 1) with three of the inexpensive “reflector lamps” carefully masked with aluminum foil or sheet asbestos so that they do not spill on the walls or ceiling of the auditorium, or shine in the audience’s eyes, or 2) by unscrewing all but three of the bulbs in the white footlight circuit, which wouldn’t be used for any other ballets on the program anyway, and placing a gelatine in front of each bulb with the desired color.

If extra spotlights were available, I would like, throughout the dance, to use three on the first light pipe and three on the second light-pipe, focused straight down with gelatins of deep blues and greens, to give an added richness of color highlight as the dancer passes through the various puddles of light. If Mr. McKenzie should also be faced with miss Anthony’s dilemma of only two available spotlights, I would suggest that he, too, place them DL and DR, focused on a diagonal, but on the floor instead of on standards. For the projections, he could use either of the methods mentioned above.

LIGHTING A PAS DE DEUX

The lighting for a grande pas de deux, while less creative than the lighting necessary for the modern and jazz dances we’ve spoken of in the first two chapters, presents problems no less demanding than those of a more interpretive dance. The problem is generally solved merely by flooding the stage with all of the available light, a most deglamourizing effect, plus a “follow spot” with a Flesh Pink gelatine that generally lags behind the dancers if they move too quickly.

February’s illustrations, I think, prove that the body form is best delineated with side lighting. This principle applies to all types of dance, but with classical ballet the side lighting must make a “perfect” wash. That is, the wash should be smooth and complete, without shadow areas or noticeable angle changes (which add interest to modern dance and modern ballet, but add confusion to classical ballet). Side lighting, furthermore, is especially important for classical ballet because of its marvelous ability to make the dancer’s legs appear slimmer and longer, and costumes and jewelry more brilliant.

Generally a little front lighting is necessary to tone down the shadow in the center of the body that results from side lighting alone, but the front lighting should be kept dim enough to permit the major illuminations to come from the side. Dim blue footlights and borderlights can be used to add a color value to the costumes especially the underside of the tutu.

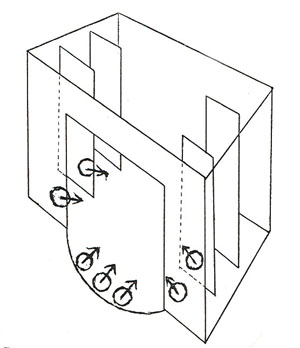

Diagram for lighting a Pas de Deux

In the “Basic 15 Spotlights” System the right, left and front washes (a total of 9 spotlights) will do the job quite adequately. If the whole program is to be devoted to classical ballet, however, I would suggest that 15 spotlights could be used in a more flexible way by mounting the 6 extra spotlights directly over the 6 wing lights on the ends of the first, second and third light pipes focused diagonally down onto the stage (angle #6, high side, in Feb.’s illustrations). By using different tints in each of the five washes, you would have a maximum in color variation.

The most practical colors for all classical ballet are Steel Blue from the side and Special Lavender from the front. These are the only colors that are flattering to all costume and make-up colors. Bastard Amber, Straw, and Flesh Pink, while providing a warm glow that is suitable for many ballets, tend to “kill” or desaturate costumes that are in the blue or green ranges, and should be used only when their disadvantages can be counteracted by enough of the “right” colors.

Generally a pas de deux should have a background of black draperies to etch the outline of the body and complement the highlights provided by the side lighting. The exception would be when the preceding and following ballets had required black draperies. In this case, a cyclorama lighted with any appropriate (but not intense) color would rest the audience’s eyes and add variety to the program.

The adagio should have softer light than the remaining parts of the ballet, primarily so that the “variations” and especially the “coda” can appear to be more brilliant by being, literally, more brilliant. Should it be necessary for reasons of visibility to have all of the spotlights at full all of the time, the effect of becoming more and more brilliant can be achieved by using the blue footlights and borderlights at a high reading for the adagio, at half for the “variations,” and out for the “coda.” The general lighting provided by the foots and borders makes the stage seem softer simply because they diminish the intensity of the highlights provided by the spotlights.

If dozens of spotlights were available, they could be used to backlight (angle #8) the center area or, if possible, the entire stage. The color could be highly theatrical since back lighting serves primarily as a halo and could not do damage to the costumes or complexions. Lemon, Blue-Green, or Magenta would all be interesting, depending on their appropriateness for specific ballet. If you’re in doubt, however, use a dark blue.

If only two spotlights are available they should be used in the DR and DL wings, as they were in the other dances discussed, and focused diagonally across the stage. If they can be raised on standards to about 8’ they will reduce to a minimum the shadows that the dancers would tend to cast on each other. The most practical colors would still be Special Lavender and Steel Blue, but for any dance where only two spotlights are used the make-up (and especially the rouge) must be very carefully blended since the Steel Blue cannot be properly complemented by the Special Lavender. With only two spotlights the dancers should rehearse very carefully to adjust their spacing so as to keep from coming either too far downstage and out of the light or too far upstage where only one of the spotlights will reach them.

(I do not mean with these discussions to imply that two spotlights will give the same results as 15 or 100. Only that it is not necessary for a dancer to “give up” and use only red, white and blue footlights when he has only a minimum of equipment. Next month we’ll go further into some of the tricks of creating the “effect of a spotlight” on a very limited budget.)

(to be continued next month)