| extended search | |||

|

|

When Everybody Called

Me Gabe-bines,

|

"This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society." "This publication was made possible in part by the people of Minnesota through a grant funded by an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. Any views, findings, opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the State of Minnesota, the Minnesota Historical Society, or the Minnesota Historic Resources Advisory Committee." |

5

Chiefs and Councils

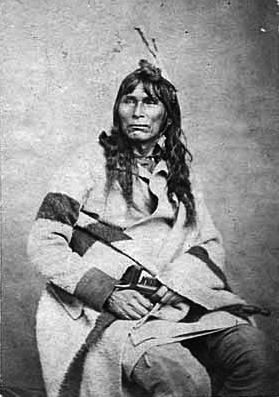

Na-bah-nay-aush (Chief One-Sided Winner), Leech Lake, ca. 1865.

Joel Emmons Whitney

Photographer: Whitney's Gallery

Photograph Collection, Carte-de-visite, ca. 1865

Collections Online

Minnesota Historical Society

Location No. E97.1N r19 Negative No. 33401 Access Number: YR1924.3693

American Indian Hunter-Gatherer-Foragers of Minnesota (REVIEW ESSAY)

-- Thomas Farrell (27 November 2022)

When my mother was just a little girl and a chief died he had a right to pass his authority on to those who were his next close relation.(1) But that's never happened too much in my time because they were always changing the customs or the constitution of the Tribe.(2) |

We had heroes in my early days, and they became our chiefs. We had different kinds of chiefs. We had family group field chiefs, and division band chiefs. Beyond that we had high-rank area chiefs, and the ogimaag great chiefs. These were all great men who lived a true life. They were men that had experience, lots of experience, and who had talked with other experienced men that went through hardships. These great men became our chiefs because they were not afraid to speak out and tell what's right! That's why in our language we called a family group chief giigidowinini, "spokesman." Our chiefs would talk and tell you the right(3) of their life. They were not afraid to talk because they went outward.

They earned what they said by going out into the world. They were not

afraid to talk because they learned through experience what they were

saying. When they'd go out into the world they'd understand the world,

understand the people, understand the hardship others went through, and

that would give them the ability to talk. Then too, they lived the life they talked about.  O-ge-mah-o-cha-wub (Mountain Chief), Chief of Leech Lake Ojibways, ca. 1860. Photograph Collection, Stereograph, ca. 1860 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.1O r6 Negative No. 34187 Most generally the family chiefs were selected from the older class that lived a life. Each had become gakiikimaa, a good "advisory-Indian," and all had proven themselves as advisors when they were scouts.(4) We evaluated them by their life, and we regularly exercised their

views by asking them questions.(5) And

when we asked them a question, they told their experience. More than

one person their ages we asked these same questions, so when they

told their answers we knew if they sounded good. If their answers were

good they agreed with those of the other older people. Finally you'd find

that they've proven themselves by their answers and by their background.

You'd realize, "That's truly a great man. He's clean, and true." When

enough people realized that, a man more or less automatically became our

family field chief.

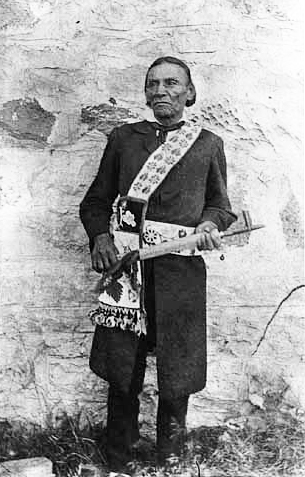

Maw-je-ke-jik (Flying Sky), Chief of Cass Lake Chippewas, ca. 1865. Creator: Whitney & Zimmerman Photograph Collection, Carte-de-visite, ca. 1865 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.1M r13 Negative No. 49719 There was a field chief to every family group. In a travelling group of relationship, a group of Chippewas, there always was a chief. Different groups here and there had a chief and each chief was responsible for his own group. From time to time, during maple sugaring, wild rice harvesting, or during the winter, many family groups would meet and camp together.(6) It was at these times that the family chiefs would meet in a general council. In these councils a chief is the same as the leader or a spokesman for his family group. He's their business man. A chief is a group's stand point in the field. He's selected from the tribe and he'll stand for what's right. He's trusted. And he has the power to go ahead and make decisions for the family group, providing that he reports back to them. And if he's not able to be at the general council, he has a second

chief -- a second assistant, a second spokesman -- to act in his place. But

the second spokesman can't go ahead and settle a deal. The family chief

has to be seen when decisions are made for his group.

And if the chief sees anything that he thinks should be done, he tells

his people, "We'll have to call a special meeting." So they have a meeting

and all go in on that. In Indian we called that little meeting of our

family group a "smoke-meeting," zagaswe’idiwin.

Later on, when I learned English, we called all of our meetings a "council."

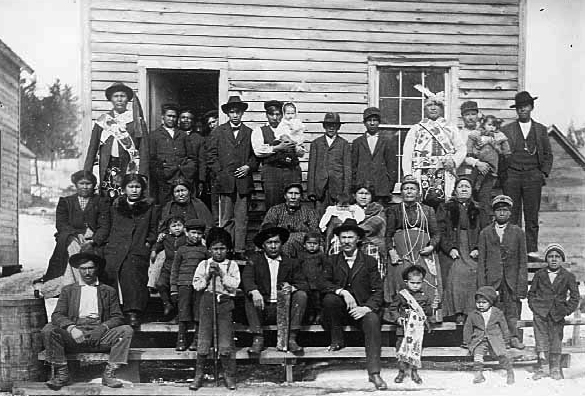

Chippewa Indians smoking in council, ca. 1900. Photograph Collection, ca. 1900 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.37 p18 Negative No. 21123 In every council they'd get tobacco out and give you a little pipefull of tobacco. You'd light that, and then you'd have a good meeting. That relaxed you, if you were in the habit form of smoking.  Elderly Indian man holding pipe, ca. 1910. Photograph Collection, Postcard, ca. 1910 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E99.1 r84 Negative No. In a local family council we talked about the point the chief brought in for discussion, or whatever we were interested in at the time. The old men used to get together and have council every day. They would plan powwows,(7) and council on a feast. They would discuss our group's plans for travel, and talk about the animals and wild crops.  Chippewa Indians at White Earth; Chief Wadena seated center, ca. 1895. Photograph Collection, Snapshot, ca. 1895 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.1W r21 Negative No. 70113

But some of those speakers still got too nervous underneath their

skin, and when they got up to speak they hesitated a little bit. That

hesitation disturbs the minds of the group, and that disturbs what they

wanted to put out to the council indirect. When your mind is easily affected

by that, your pronunciation of the points you're talking about in the

meeting is disturbed. It's difficult to speak before a council, and that's

one of the reasons our good speakers became our leaders.  Indian council, White Earth, ca. 1873. Creator: Hoard & Tenney Photograph Collection, Stereograph, ca. 1873 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.5 r6 Negative No. 34859 In any council not everybody talked -- but everybody listened. Sometimes it seemed like only some had a voice, but that was all right, because if you'd just go and listen, you were still learning. Some people only listened all of the time. Good listeners became good advisors to the group. When a man listened to what the action was in all of the councils we called him obizindaan. That was the same as calling him an advisor in our language. If he listened to what they were discussing, and it all was clear, very well. But if he saw something wrong, or some danger, and was puzzled, he'd speak up and ask the group what they meant. I wasn't afraid to ask questions to the older class. Many, many things I've seen in my time, and I understood them. Why? I think I understood them because I asked questions and it was explained to me. I wasn't stuck very often, but a lot of times I asked what something meant. When we kids went to a meeting we usually just listened, but if we had a question or thought we had a good point, we'd bring it out.(8) By doing this we learned and had a voice in these meetings. If we didn't do it right the people at the meeting just bypassed us. They probably had better points, but that was all right because we were learning. Councils calling the others in for their words were always a big thing in this Indian country of ours. A meeting, a gathering, is a great thing. When you get through with a meeting you feel good. And when you go out into the field after a meeting's over you begin to see things differently because you heard something. You learned something by others talking. Their points meant a lot to you. It's a great thing to get together -- an important thing -- so when you say anything, be careful, always. I was always glad to join any meeting. That's the way we all joined hands to work together. I liked to sit and listen to the others make their points. Why? Because that's where I was learning by the experience of others' lives. They have experience just as well as I have. Maybe they have problems, and maybe these problems could be threshed out in the meeting. Maybe the problems could be clearified for a better way of life. That's what the meeting was for -- to understand one another, to listen to one another. A meeting was not held to say that a person was wrong or right. Sure, we helped one another by pointing out problems, but at the meetings we worked hard just to understand others' points. That's what I noticed as a boy, and that's pretty much what I've seen happen at councils all my life. In my canoe days(9) our chiefs would come to a general council from Leech Lake, Mud and Goose Lakes, White Oak-Mississippi-Ball Club, and sometimes from Boy River, and Winnibigosh. There were usually a couple chiefs that would come from Leech Lake. These places were the main divisions of my area at that time. In Indian we called these divisions endanakiid, "that's-where-he-works." In English these divisions were called "bands." We went by bands in those days. We had bands, but whites didn't recognize these bands as legal. Each band -- like my Mississippi Band of the Mississippi River -- had

its own district. What we called the Mississippi Band had the area around

White Oak, Bena, Ball Club, Inger, and Squaw Lake; that's the area of the

Mississippi Band. There were other bands at places like Leech Lake, Cass

Lake, and Mille Lacs.

Then there was also a band enrolled at White Earth. They took a treaty settlement at White Earth. "Removable Indians," we used to call them, because their old timers moved to White Earth. As part of their treaty settlement they took horses; they took farm implements. They were always looking for a final settlement, and I remember they fought for final settlement with the U.S. government. But for some reason the U.S. government never did give them a final settlement on account of the treaties of old time, the treaties of a fifty-eight year period.(10)  Mille Lacs removals with their chief at Big Elbow Lake, ca. 1905. Creator: Robert G. Beaulieu Photograph Collection, ca. 1905 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.5 r4 Negative No. 32977

The division or band chiefs were most generally the oldest and most

respected family chiefs of the districts. When the Indians had large gatherings

in their seasonal camps, they'd discuss who were the family chiefs. The

locals discussed them. "There is a good man," they'd say. They knew their

men. Some men didn't have any faults in their backgrounds. These men were

clear. They were known for their honesty. They showed their ability by

their background. The families they raised proved what they had done,

and it was great. So they just naturally became the band chiefs. They

just naturally became the spokesmen for the bands and we called them a giigidowinini, just the same as we called a spokesman in

a family group. These band chiefs were the ones that most often spoke

up at a general area council.  Chippewa chief White Cloud (Waabaanakwad), Gull Lake, Leech Lake (after 1862), and White Earth (after 1868), ca. 1895. Photograph Collection, Cabinet photograph, ca. 1895 Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Location No. E97.1W r19 Negative No. 4721

Quite naturally, from these general councils, certain band chiefs

got to be well-known as good speakers and leaders. They became what we

called chi-giigidowinini, a "spokesman in a high

rank." These high-rank spokesmen became the main leaders for our areas.

That's how we picked our chiefs. I was there. I know that. I've seen that.

I remember Gebejiwan -- "River-Flowing-All-The-Way" -- and Bezhigogaabaw -- "Standing-Alone" -- and Chief Greenhill. These high-rank chiefs didn't take all the responsibility for their areas themselves. They had councils with the locals and the band chiefs, and by their Indian words they'd more or less vote. When all band chiefs got together and some chiefs found a weakness, the high-rank chief always explained it with very good points. Other chiefs went along with him.

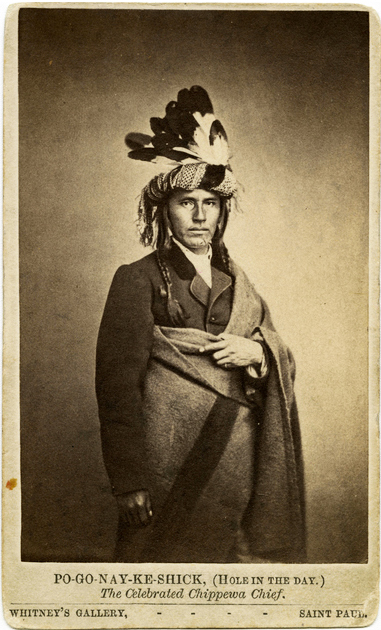

Our area chief represented the Winnibigosh, Mississippi, and Leech Lake Bands. He was generally stationed at Leech Lake and you were free to go there and see him. Leech Lake is our reservation and our high-rank chief was there. If you wanted to find out something, he'd tell you the truth. He was glad to show you where to camp, and where the best place was for fishing and for berries. I don't remember too much about our high-rank chiefs. I only remember who they were and how they got to be chiefs. I do remember my mother talking a lot about Chief Hole-in-the-Day,(11) and, of course, about my grandpa Chief Buffalo.  Po-go-nay-ke-shick (Chief Hole in the Day, the Younger), ca. 1865. Photograph Collection, carte-de-visite, ca. 1865 Photographer: Whitney's Gallery Collections Online Minnesota Historical Society Accession No.: YR1941.5098 Negative No. 10543 Identifiers: E97.1P r17 Chief Buffalo was what we call ogimaa, a great chief. He was a well-known leader and spokesman of the Chippewa nation from Wisconsin.(12) Most Indian people knew him as Bizhiki. As one of the great chiefs of the Great Lakes, my grandpa signed a lot of the treaties of the 1880s. He signed the Rice Treaty and everything. My mom told me, and my grandpa and my uncles from Wisconsin told me, "He was a great chief. He was a great chief of all. He kept the Indians together with peace, and he was respected. He kept the state clean. He was a chief that the other chiefs respected, and as a chief they give him authority to take a tract of land of a hundred and sixty acres for his own private ownership." In Chief Buffalo's times the Indians were having a little trouble. They were having some problems, one family to another, once in a great while! Chief Buffalo went through northern Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota, around Duluth, with ministers, to see the Indians. He'd peace-talk with them, and settle with them. He'd talk with them and give them lands through the U.S. government's allotment program. He walked through that area and did that, and they quieted down. When they got their allotments each family had their own place. That's how they calmed down. Chief Buffalo made peace among the Indian people by arranging for land ownership through allotments and by speaking out as a great chief. I know too that he took land in Wisconsin for the group reservation area, and for his own land he took Duluth and some property in Ashland. He took Duluth for his private family, for his private family enterprise. The way I feel is that the chief was supposed to have from the tribe one mile square of land for his people, for his relatives. That's how he got the property in Ashland and the property where the Glass Block department store now is in downtown Duluth.(13) Chief Buffalo adopted a white man named Armstrong(14) and it reads in the book at the Indian office that he signed his land

over to his adopted son. Chief Buffalo thought a lot of the white people

and that might be one of the reasons he adopted Armstrong. He thought

a lot of the sailors(15) especially. He thought that the white people were

showing us a better way of life. Some thought we weren't ready to handle

our own affairs at that time because there was so much pressure from the

people who were coming in to our area. So maybe that's why he adopted

that boy into the tribe. Well, maybe he had a reason. Maybe that was his

own boy. You can't tell, you know. I can't tell you that, but maybe it

was his own boy. In that matter I couldn't explain how Armstrong

was adopted either, but Chief Buffalo did adopt him.

Benjamin G. Armstrong. Source: "The Incredible Journey of Benjamin Armstrong and Chief Buffalo" National Park Service Armstrong was a white man so he probably got a chance to take most of Chief Buffalo's land, and did, which he shouldn't have done. If he was adopted he shouldn't get any land, or he shouldn't have taken it all. Armstrong should have divided it up. There were a lot of claims and claimants with Chief Buffalo from the Indians of our people, for he left twenty-three children and grandchildren behind him. Land problems aside, all of Chief Buffalo's relatives I met spoke of him as a great leader of our people. So has everyone else. That's why he was an ogimaa chief. The great chiefs of the Chippewa nation met together and talked things over too, usually at treaty-making or treaty-payment time. They held council the same way others did, giving speeches and exchanging views by talking with one another. My mother and my aunt Betsy from Wisconsin always told about the great speech Chief Buffalo made at a gathering of Great Lakes Indians. It was about 1826, somewhere in there, and I think it was in Duluth. Chief Buffalo called all the chiefs in beside him. There was an ogimaa chief of the tribe in every area along the Great Lakes and along the Mississippi in those days. Chief Buffalo spoke to six or seven ogimaa chiefs and the people who came with them, and to the government officials who were there. He spoke:

There was one, as I understand, one chief who said, "How are we going to live in this country? How are the children going to live without education? The white men are coming in this country. And there's going to be a development. Are our children going to understand the development? Are they gonna be trained?" One chief said, "Yes! We're going to have schools. We're going to have teachers. We're going to have representatives that will work with us. They're going to give us that." Another chief jumped up. He said, the other chief said, "Is it so that we could go along without school?" The last chief said, "It's proven right now that across the ocean they have big boats coming across. And they can build those big boats with their own skill, and they'll be here. As far as you can see across the ocean there'll be a white man coming into this country! That's how many white people are coming. Should we pick up our arms? I don't think it's right." That's what he said. "So we shouldn't fight. Maybe they're coming to learn us a better way of life." So that great Chief Buffalo said,

They all went home and told that big speech to others. They looked forward to that what Chief Buffalo predicted, and before long, there it was. Pretty soon they felt what Chief Buffalo was talking about and predicting as the white people started moving into the area. East, and west, and south came in. Chief Buffalo was a predictor, a commentator on what was going to happen. The Indians respected his words, and the others began to realize that this is Indian country. The history of that chief is great. He predicted that stuff and that's how he got to be a chief. That's why he was a great man, and that's why they all called him Ogimaa Bizhiki. I was always

sorry that I never knew my grandfather Bizhiki because I thought

of him and his predictions a lot as I watched and listened on our family

travels.  Chief Buffalo's Grave, La Pointe, Madeline Island, Wisconsin. Bizhiki b. ca. 1759 - d. September 2, 1855 Source: "Kechewaishke" -- Wikimedia 1. Chieftainship was inherited in the old days, but a chief's power and influence was, in effect, based on his personal characteristics and his ability to engender consensus among his group(s), including the women. 2. Later on leadership became elected. See League of Women Voters of Minnesota, Indians in Minnesota (North Central Publishing Co., 1974); Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Curriculum Development Staff, Minnesota Chippewa Tribal Government -- Student Handbook (Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, 1978); Bruce White, We are at Home: Pictures of the Ojibwa People. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Press, 2007, Ch. 2, "Ogimaag / Leaders"; and cf. James G. E. Smith, "Leadership Among the Southwestern Ojibwa," National Museums of Canada, Publications in Ethnology, 7 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1971). 3. Where they went right in life, and did the right things. 4. See Ch. 4, "Siouxs and Scouts." 5. For a discussion on asking elders questions, see Ch. 40, "John Smith 'Wrinkle Meat,'" and Ch. 11, "Campfire Talks." 6. See Ch. 6, "Spring Move to the Sugar Bush," Ch. 7, "Skigamizigewin, Maple Sugar Time," Ch. 11, "Campfire Talks," Ch. 13, "Manoominike-Giizis, 'Wild Ricing Moon,'" and Ch. 18, "Late-Autumn Winter Camp." 7. See Ch. 23, "Niimi'idiwin: 'Come and Dance, Come and Sing -- Living and Spirit Alike.'" 8. See Ch. 40, "John Smith 'Wrinkle Meat'" for details on the customs involving young people asking questions in a group situation. 9. See Ch. 3, "Canoe Days." 10. For a list of the "Major Federal Treaties, Laws and Other Actions" affecting the Minnesota Chippewa peoples beginning in 1825, see League of Women Voters of Minnesota, Indians in Minnesota (North Central Publishing Co., 1974), "Appendix," pp. 181-196. See Also Ojibwe > Ojibwe Treaties (Wikipedia) for a list of treaties, organized by treaty partners. 11. See Julius T. Clark, "Reminiscences of Hole-in-the-Day," Wisconsin Historical Collections, 5 (1868), 378-401; Mark Diedrich, The Chiefs Hole-in-the-day of the Mississippi Chippewa (Coyote Books, 1986); Stephen P. Hall, "The Hole-In-The-Day encounter," The Minnesota Archaeologist 36:2 (1977), 77-96; G. W. Sweet, "Incidents of the Threatened Outbreak of Hole-in-the-Day," Minnesota Historical Society, Collections, 6 (1894), 401-408; and Pauline Wold, "Some Recollections of the Leech Lake Uprising," Minnesota History, 24 (1943), 142-148. 12. There are three notable individuals called "Chief Buffalo" among the Anishinabe/Chippewa/Ojibwa peoples: Chief Buffalo or Kechewaishke [Gichi-waishke] (1759–1855), Ojibwa chief of the La Pointe Band of Lake Superior Chippewa; Buffalo, an Ojibwa chief of the St. Croix Band; and, Beshekee (Buffalo), an Ojibwa chief of the Leech Lake Band. ("Chief Buffalo," Wikepedia.)

13. The old Glass Block department store in downtown Duluth, which closed in 1981, not the Glass Block formerly at Miller Hill Mall, which closed in 1998.

14. Benjamin G. Armstrong. See John O. Holzhueter, Madeline Island and the Chequamegon Region, (State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1974), and National Park Service, "The Incredible Journey of Benjamin Armstrong and Chief Buffalo." Accessed 27 June 2018. https://www.nps.gov/apis/learn/historyculture/armstrong.htm. 15. People who worked and traveled on the Great Lakes. 16. I.e., new ways to plant corn; better ways to plant corn. |

| to top of page / A-Z index |

This site is under construction. Comments  E-mail comments

to troufs@d.umn.edu E-mail comments

to troufs@d.umn.edu The University of Minnesota Copyright: © 1997 - 2021 Timothy G. Roufs |

The views and opinions expressed in this page are strictly

those of the page author ![]() .

.

The contents of this page have not been reviewed or approved by the University

of Minnesota.

Page URL:http://www.d.umn.edu /cla/faculty/troufs/Buffalo/PB05.html

Last Modified

Tuesday, 29-Nov-2022 11:38:52 CST

Department of Studies in Justice, Culture, & Social Change ![]()

College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Science ![]()

215 Cina Hall ![]()

University of Minnesota Duluth (maps) ![]()

Duluth, MN 55812 - 2496 (maps) ![]()

Gitchee-Gumee

Live ![]()

| to top of page / A-Z index |